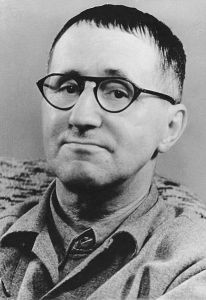

Damn, damn, damn! Here I am, a day after attending an absolutely brilliant reading of new translations of Bertolt Brecht’s love poems, able only to find the German original online of the piece that absolutely knocked me to the floor last night.* And, conscientious translator that I am, I realize it’s technically illegal for me even to essay a private attempt at rendering the thing into English without prior permission. But since it’s been easy to find the verse auf deutsch all over the blogosphere (and since page 28, on which the poem in question, “To M,” is found, is conveniently unavailable for viewing on Amazon), I’ll paste it at the end of this post, so that you can get the full pathos and suck up every last umlaut if you so desire.

You realize what this means, of course. I’m going to have to buy another book, damn it, when I already have enough of a problem keeping my wallet chastely closed whenever a purveyor of fine print material happens to give it a come-hither wink.** And when I’ve got the hot little volume in my hands, maybe I’ll quote some of the amazing lines from this unexpectedly hard-tender lament, whose teller lets in the whores and beggars and rabble because the “you” so desperately needed inside isn’t standing around waiting to get in, and an empty ache needs to be filled at any cost.

It almost reminds me of the parable of the wedding banquet in Matthew 22, where the invited guests decline to drag themselves to the celebration, so the king tells the servants, “‘Go therefore into the main streets, and invite everyone you find to the wedding banquet.’ Those slaves went out into the streets and gathered all whom they found, both good and bad; so the wedding hall was filled with guests.” (NRSV) There’s more to the parable than that, and it gets weird and uncomfortable, as is often a biblical parable’s wont. I don’t know enough about Brecht even to wonder whether he was making any sort of allusion here– but I get the feeling he wasn’t. It’s just long heartache, pure and simple, on the other side of which is a numb acceptance or resignation or successful conditioning into submission thanks to prolonged schooling in reality.

Well: until I’ve gotten a hold of the new volume, I’ll leave you with a beautiful runner-up that is available for preview. Behold, “Sonnet No. 19”:

One thing I do not want: you flee from me.

Complain, I’ll want to hear you anyway.

For were you deaf I should need what you say

And were you dumb I should need what you see

And blind: I’d want to see you nonetheless.

Given to watch for me, companion

The way is long and we’re not halfway done

Consider where we are still: in darkness.

“Leave me, I’m wounded” is not good enough.

And nor is “Somewhere,” only “Here” will do.

Take longer with the task: but you can’t be let off.

You know, whoever’s needed is not free.

But come whatever may, I do need you.

I saying I could just as well say we. ***

* While undertaking this futile search, it was made painfully plain to me that something limiting has gone on with the diffusion of Brecht’s poems in English. On site after site, I found the same selection of poems, with hardly any variation. The guy wrote hundreds of pieces, and everyone just decides to stick to the same few featured in anthologies?

** Hell, even before going to the reading, I threw down some scarce cash for Junot Díaz’s This Is How You Lose Her and Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers. I guess I could make myself feel better by reminding myself that 1) I could be buying street drugs, and/or 2) a person can’t live by bread alone, & etc. Still, the ability to make rent and utilities is not an overrated experience.

*** Bertolt Brecht, Love Poems, translated by David Constantine and Tom Kuhn (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2015), 86.

In jener Nacht, wo du nicht kamst

Schlief ich nicht ein, sondern ging oftmals vor die Türe

Und es regnete, und ich ging wieder hinein.

Damals wußte ich es nicht: Aber jetzt weiß ich es:

In jener Nacht war es schon wie in jenen späteren Nächten

Wo du nie mehr kamst, und ich schlief nicht

Und wartete schon fast nicht mehr

Aber oft ging ich vor die Tür

Weil es dort regnete und kühl war.

Aber nach jenen Nächten und auch in späteren Jahren noch

Hörte ich, wenn der Regen tropfte, deine Schritte

Vor der Tür und im Wind deine Stimme

Und dein Weinen an der kalten Ecke, denn

Du konntest nicht herein.

Darum stand ich oft auf in der Nacht und

Ging vor die Tür und machte sie auf und

Ließ herein, wer da keine Heimat hatte.

Und es kamen Bettler und Huren, Gelichter

Und allerlei Volk.

Jetzt sind viele Jahre vergangen, und wenn auch

Noch Regen tropft und Wind geht

Wenn du jetzt kämest in der Nacht, ich weiß

Ich kennte dich nicht mehr, deine Stimme nicht

Und nicht dein Gesicht, denn es ist anders geworden.

Aber immer noch höre ich Schritte im Wind

Und Weinen im Regen und daß jemand

Herein will.

(Obgleich du doch damals nicht kamst, Geliebte, und ich

war es, der wartete -!)

Und ich will hinausgehen vor die Tür

Und aufmachen und sehen, ob niemand gekommen ist.

Aber ich stehe nicht auf und gehe nicht hinaus und sehe nicht

Und es kommt auch niemand.

1922