Sidetracked by the Trivial

Having somehow put four decades of mostly American existence behind me without having read Carson McCullers’s The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, I decided to remedy that situation after experiencing one of those weird coincidental combinations of events: namely, having a review of said book showing up on my desk, and my mom sending me one of her spare copies of the novel a couple of days later. The universe threw down its challenge, and I decided to accept it.*

I’m not big on “Southern” writers,** so my “it was OK” rating probably isn’t worth much. Poverty, punishing heat, a particular variety of racism, the predictable presence of semi-mad loners trying aggressively to convert people to Jesus and damn those not open to such a gift: although I didn’t grow up in the deep South, I was close enough to it in my childhood, and lived in enough parts of it as an adult, for many of these authors’ pieces to feel like anything but fiction.***

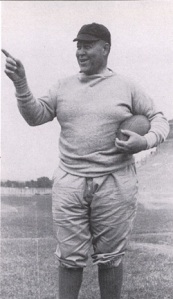

A real person actually called Biff. Photo from 1940- the same year Lonely Hunter was published. Via Wikimedia Commons.

That’s about as far as it goes for my thoughts on the book as a whole. But the silly question that’s really refused to leave my head is this: was anyone ever really called Biff? Sure, you’ve got the character here, another one of the same name in Death of a Salesman, maybe a few more in some 20th-century movies– but I’ve never come across any actual individual who got stuck with that nickname. Maybe it’s because the handle seems so definitively time-bound; calling someone “Biff” these days would seem to be an obvious throwback or bit of yearning for the past– but even then, would a present-day usage-as-nostalgia-trip be meaningful at all, if the name never really made its way out of fictional realms? Here’s a hypothetical: if the nickname “Biff” never was in (widespread) actual usage (and I’ve no idea whether or not that was the case), what does it mean to have a particular name pop up in such an essential sampling of our national literary heritage? Might we be prey to a societal yearning for nicknames themselves, a sort of desire for community that often only gets fulfilled in fiction, where people know each other well enough, or at least feel comfortable enough with each other to believe they do, to rebaptize their fellows with monikers ideally suited to their personalities?

Admittedly, I’ve had a number of uncles who got slapped with classic good-ol’-boy nicknames, raised as they were in the same atmosphere that trained George W. Bush in being able to whip out instant sobriquets for journalists and cabinet members alike. But I’ve also known at least one relative who wanted so badly to be part of that sort of inclusive teasing that, late in life, he’d just start introducing himself by the fishing-related term he wished others had started calling him of their own accord years ago.

I’m not sure I should admit to the fact that this question of a particular nickname is what struck me the most about McCullers’s book; for example, I should be more amazed than I am that the author was a mere twenty-three years old when it was published. And sure, there are the questions it poses about what it is we need and want from other people, who we expect them to be for us, and our blindness to our own recreation of their images in our own. But sometimes, as was the case with my own reading of the story, when you’ve been confronted with pretty much the same setting and characters one too many times, the one thing that stays with you is entirely, insignificantly peripheral to everything you were supposed to take away from the tale.

* Only after devouring the third volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle– and really, what can I say about that other than “Yum”?

** The prime exception being William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. I’ve also grown more appreciative over the years of Flannery O’Connor’s writing as writing, but it’s still difficult for me to face her characters, whom I know.

*** Why, then (and in line with the previous note’s observation about O’Connor), can I not just celebrate these writers’ ability to present a truthful portrayal of people and places?

Such an interesting commentary on your experience of reading the book and the impression it leaves, that peripheral aspect of nicknames, I love the picture of the man actually named Biff.

I’m intrigued by what you say about the familiarity of stories that make them less interesting, are we as readers looking to understand ourselves or the other or something entirely different. I know I gravitate away from the familiar, to the point that I am more interested in literature in translation than that written originally in English.

A thought-provoking post!

LikeLike

Many thanks!

I think one of the signs of a great-to-me writer is someone who can take the familiar and reveal a new aspect or depth about it– maybe not quite equivalent to making the old new again, but more like removing a blind spot that had prevented us from seeing something or thinking about it in a certain way. David Foster Wallace’s representations of American culture in general tend to do that for me– especially Infinite Jest, which I think was able to portray the absurdities of (among other things) American consumer culture in a way that no one had ever done before (or has done since, I’ll allege).

LikeLiked by 1 person